The purpose of this blog post is to inform our followers of a slight modification in our project. This modification, but we should call it zeroing instead since we are narrowing our focus, came after discussing our project with Dr. Kalidindi.

We have decided to focus now on a very specific type of grain growth: we will be looking at “pinned” grain growth. This is the phenomenon that occurs when a distribution of insoluble precipitates is added to the microstructure of interest.

I will start by giving a brief background theory regarding grain growth. The driving force that causes a grain to grow is the interfacial grain boundary. In an ideal world all the grains grow at the same rate. Thus an increase in the average grain size will also imply the disappearance of some grains, usually the smaller ones, since the sum of the individual grain sizes is a constant number.

The addition of insoluble particles affect grain growth since they “pin”, i.e. deter, the growth of a grain because they reduce the surface area when a boundary crosses path with it. Other researchers have been adding these precipitates to metals with the desire to control the final grain size of the microstructure. Even though this is a well-established practice the theory of it is still not well understood.

Please refer to these two and papers if you want a deeper understanding of the theory of Grain Growth (paper 1, paper 2). We suggest these papers since are the ones our team used as a literature review to understand grain growth and also detail with the theory of grain growth with precipitates.

The main points of these papers are the following:

- There is a critical radius size for the precipitates that allows for a pinned grain to grow dependent on:

- Volume Fraction of the precipitate

- Heterogeneity of the matrix

- Matrix grain size.

- There is a critical ratio between the sizes of neighboring grains that will allow a grain to grow.

- There are 2 critical sizes on the grain that will allow for a grain to grow normally, at the same rate as their neighbors, or abnormally, at a faster rate.

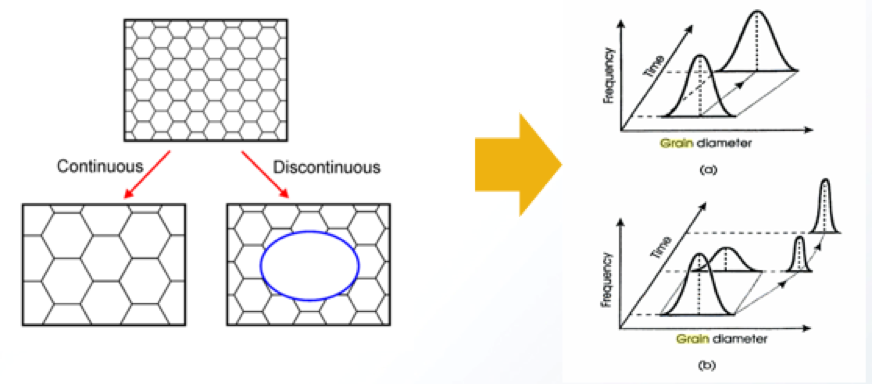

As mentioned before precipitates affect the growth rate of a microstructure and can cause abnormal growth which can eventually lead to a abnormal distribution of grain size. The following image depicts it very clearly.

Furthermore, theory does mention mentions how a distribution of precipitates will affect the final grain size—it just mentions some vague ratio about size.

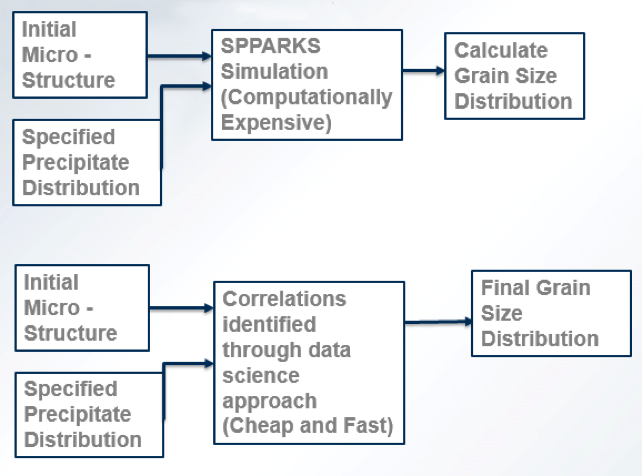

Therefore the current way to know what the final grain size distribution will be is to generate a microstructure, input it in SPPARKS (see previous blog posts to learn more about this open-source code) and finally calculate that grain size distribution.

The goal of our project is now to use Data Science approach to identify the correlations between a certain distribution of particles and its final grain size distribution.

The following image sums up this goal.

Please be on the lookout for the next posts since we will detail the distributions of precipitates used and also our preliminary results regarding our first simulations.